The criminal element in our society is like a parasite. It resists extermination and must be tolerated, as long as its damaging impacts can be minimized. Experienced law enforcement officials will tell you that these criminals are also highly organized, very sophisticated, and use the latest in technology to exploit their hosts. Unfortunately, these crooks also need to move huge sums of capital about the global scene, and, in order to do this effectively, they need the global banking community to serve their needs.

These organized crime groups cloak their activities in clever disguises that we today term as money laundering. In many cases, they leverage a broad network of unsuspecting banks within the developing sector of the global economy. Banks that exist in tax havens or in emerging economies tend to be less strenuous in their monitoring and regulatory procedures, the perfect environment for illicit money movements. There are many schemes that have been used to launder funds, but the majority of them involve international money transfers to some extent to camouflage their actual source.

As forex traders, we are well aware of the implications of Anti-Money Laundering (AML) standards to the cfd provider industry. Every broker and provider requires that specific personal identity information be on file and current, a basic requirement that international regulators have mandated for rudimentary compliance. The recent Plus500 Fiasco, where regulators punished them for insufficient AML documentation, is one case in point. After staff at Plus500* missed a critical deadline for remediation of missing documents, the FCA froze client accounts and new account solicitations. The firm’s stock price was cut in half after this news broke, a paper loss of $650 million to shareholders of record.

*81% of retail investor accounts lose money when trading CFDs with this provider. You should consider whether you can afford to take the high risk of losing your money.

What is Money Laundering and what methods do crooks employ?

Money Laundering is nothing new, but it gained enormous awareness following the 9/11 terrorists attacks on the New York Trade Center. Government officials the world over suddenly adopted new laws, designed to thwart the flow of funds to terrorists groups. These laws also had the double benefit of hitting the criminal element where it lived. It had been operating in the shadows, well outside of the public eye for countless decades.

Whether the criminal largesse was obtained through extortion, illicit arms deals, drug trafficking, insider trading, illegal gambling, or any of a host of other crimes, the monies were considered “dirty” by the financial establishment. The simple solution was to “clean” the funds in such a fashion that banks and other entities would not become suspicious and question the dealings of the account holders. As financial institutions evolved into the electronic age, money laundering also took on a more complex and sophisticated profile, utilizing several different methods to produce the desired result.

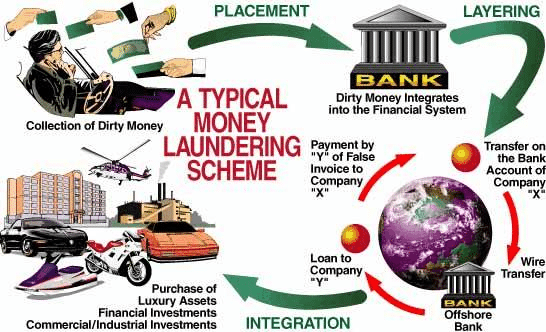

The definition of money laundering has also been updated and is no longer considered a minor element of a broader region of financial crime. According to the U.S. Treasury Department, “Money laundering is the process of making illegally-gained proceeds (i.e. “dirty money”) appear legal (i.e. “clean”). Typically, it involves three steps: placement, layering and integration. First, the illegitimate funds are furtively introduced into the legitimate financial system. Then, the money is moved around to create confusion, sometimes by wiring or transferring through numerous accounts. Finally, it is integrated into the financial system through additional transactions until the “dirty money” appears “clean”.” The following diagram illustrates a typical scheme:

The banking community obviously plays a major role in the process. As to the size of the problem, no one has ever been able to produce reliable estimates, but twenty years back, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) surmised that these illegal funds could actually make up 2% to 5% of the global economy. The Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF), a cooperative body founded in 1989 by G7 countries to combat money laundering, has said that, “Overall, it is absolutely impossible to produce a reliable estimate of the amount of money laundered and therefore the FATF does not publish any figures in this regard.”

In any event, the size of the problem, if the IMF is anywhere near correct, approximates the level of fraud that is tolerated in many forms of financial services. While awareness and responses on the legislative front have escalated, banks have been complaining that the costs to enforce these laws are not worth the effort. The Economist has proclaimed the effort to be a “costly failure” and has estimated “the annual costs of anti-money laundering efforts in Europe and North America at US$5 billion in 2003, an increase from US$700 million in 2000.” Legitimate capital formation has suffered.

What are banks supposed to do and expect from their customers?

The basic approach that bankers take is to fiercely obey what are commonly referred to as “Know-Your-Customer” or “KYC” rules. Banks are supposed to learn everything about a new customer that goes well beyond the customary handshake. They need to understand the nature of your business, your previous experiences, your customers, and what your deposit and expense trends might resemble. They load all of these items into monitoring and screening software that is designed to detect anomalies. Upon researching these, they may be required to file a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) or question you directly about what might be transpiring.

The only problem with this approach is that the crooks are well aware of every step in the fraud prevention process. They will deliberately structure their deposits to fall within acceptable limits or break down cash receipts into smaller amounts to avoid detection, a method called “smurfing”. Criminals will also create over-stated invoices, borrow against them from the bank, and then have funds wired in from offshore directly to the bank, as if another entity is paying for its products or services.

What are a few examples that illustrate how easily banks have been duped?

In order for money laundering to occur, a compliant bank must be found and leveraged. How do the crooks find these compliant banks? Believe it or not, it is not that difficult. There is always an eager bank looking to grow deposits quickly and make its mark in commerce. Organized crime understands how the game is played. They will typically find a local bank, either in a developing country or offshore tax haven, and test their oversight procedures. If they are able to land a larger, more prominent bank that is willing to look the other way, then so much the better. The word will spread quickly, and the cooperating bank will soon find that it got much more than it bargained for.

The past is riddled with banking scandals in this area. The bank that really got the AML ball rolling for law enforcement and regulatory officials was the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI). It was founded in 1972, ostensibly to be the bank for developing nations across the globe. Agha Hasan Abedi, a Pakistani financier, was behind the venture, and, by the eighties, he had built a sprawling network of “over 400 branches in 78 countries, and assets in excess of US$20 billion, making it the 7th largest private bank in the world.”

Regulators, however, were becoming increasingly concerned that illicit operations had taken over the bank, making it a target for criminals and questionable loan practices. U.S. and UK investigators surmised that, “BCCI had been set up deliberately to avoid centralized regulatory review, and operated extensively in bank secrecy jurisdictions. Its affairs were extraordinarily complex. Its officers were sophisticated international bankers whose apparent objective was to keep their affairs secret, to commit fraud on a massive scale, and to avoid detection.”

After a protracted regulatory battle over jurisdiction, regulatory officials in seven countries raided and shut down the far-flung offices of BCCI on July 5, 1991. The bank had opened accounts and openly laundered money for the likes of “Saddam Hussein, Manuel Noriega, Hussain Mohammad Ershad and Samuel Doe, and for criminal organizations such as the Medellin Cartel and Abu Nidal.” Fraudulent loans of some $5 billion had zero documentation, but, by 2007, depositors were finally able to recover 75 cents on the dollar.

Has much has changed since then? Here are a few more recent snippets of major banking defalcations:

* Bank of New York – Got caught laundering $7 billion in illicit Russians funds in the late nineties;

* Hong Kong Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) – Paid over $1.9 billion in fines in 2012 for aiding drug runners, terrorists, and sanctioned governments to launder hundreds of millions of dollars;

* Liberty Reserve – Innovative Costa Rican bank that ignored KYC rules and was shut down for laundering over $6 billion in 2013;

* BNP Paribas – Fined $8.9 billion in 2014 after pleading guilty for falsifying records and violating U.S. sanctions by moving funds to and from Cuba, Iran, and Sudan;

* HDFC Bank and Bank of Baroda – Recently in October, two of the largest banks in India were complicit in a $1 billion money laundering operation, involving over 100 accounts and the funneling of money to more than 400 partners in Hong Kong. The scheme was designed to overstate imported goods on invoices, to evade custom duties, and to receive favorable trade tax credits. The crime was discovered when the cross-border payments did not match up with related food imports of rice, cashews, and other foodstuffs.

The latter example illustrates how elaborate the placement and layering aspects of money laundering can be, once an unsuspecting bank has been located and duped. In this case, management teams at both banks have now committed to enforce improved KYC norms within their respective institutions, actions that are a bit late. The crooks, however, have moved on to their next banking prospect.

Concluding Remarks

The next time your forex broker requests an update of your AML documentation, try to be a little more understanding of the need for the process, even if it is inconvenient. In the absence of an appearance of compliance, criminals will quickly pounce upon the unsuspecting broker, flood it with new deposits, only to be transferred or withdrawn at a later date, as part of an complex placement and layering process.

A regulatory scandal, as with Plus500* in London, could then result, freezing your assets for an undisclosed period of time. You might also want to be wary of brokers in tax havens or exotic locations, far from any regulator’s peering eyes. They may have every intention of being legitimate, but the criminal element gravitates to these places, as well, and an ensuing forex scandal could ruin their day and yours in an instant.

*81% of retail investor accounts lose money when trading CFDs with this provider. You should consider whether you can afford to take the high risk of losing your money.

Related Articles

- Forex vs Crypto: What’s Better For Beginner Traders?

- Three Great Technical Analysis Tools for Forex Trading

- What Does Binance Being Kicked Out of Belgium Mean for Crypto Prices?

- Crypto Traders and Coin Prices Face New Challenge as Binance Gives up its FCA Licence

- Interpol Declares Investment Scams “Serious and Imminent Threat”

- Annual UK Fraud Audit Reveals Scam Hot-Spots

Forex vs Crypto: What’s Better For Beginner Traders?

Three Great Technical Analysis Tools for Forex Trading

Safest Forex Brokers 2025

| Broker | Info | Best In | Customer Satisfaction Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 |

|

Global Forex Broker |

BEST SPREADS

Visit broker

|

||

| #2 |

|

Globally regulated broker |

BEST CUSTOMER SUPPORT

Visit broker

|

||

| #3 |

|

Global CFD Provider |

Best Trading App

Visit broker

|

||

| #4 |

|

Global Forex Broker |

Low minimum deposit

Visit broker

|

||

| #5 |

|

Global CFD & FX Broker (*Don’t invest unless you’re prepared to lose all the money you invest. This is a high-risk investment and you should not expect to be protected if something goes wrong. Take 2 mins to learn more) |

ALL-INCLUSIVE TRADING PLATFORM

Visit broker

|

||

| #6 |

|

Global Forex Broker |

Low minimum deposit

Visit broker

|

||

| #7 |

|

CFD and Cryptocurrency Broker |

CFD and Cryptocurrency

Visit broker

|

||

|

|

|||||

Forex Fraud Certified Brokers

Stay up to date with the latest Forex scam alerts

Sign up to receive our up-to-date broker reviews, new fraud warnings and special offers direct to your inbox